Jacques Guerlain: Complete Biography of a Perfumery Genius

This post is the translation of an enormous work realized by Will INRI (a Guerlain and Perfume history enthusiast, a brilliant young man!) for Wikipedia; I translated, shortened, slightly modified, and completed it when I could.

I admire Jacques Guerlain’s work greatly; I have worn L’Heure Bleue for many years and never tire of it. It is a tribute to thank him for offering me this masterpiece created in 1912.

As I am currently watching the series Mr. Selfridge, a saga about the creation of the Selfridges Department Store in the UK, where Guerlain is honored (it is in the same style as Downton Abbey), it made me want to honor this great Perfumer, I would even say this genius.

Jacques Guerlain: The Man and the Work

Jacques Edouard Guerlain (October 7, 1874 – May 2, 1963) was a French perfumer, the third and most famous of the Guerlain family. He was one of the most prolific and influential perfumers of the 20th century.

More than 80 Guerlain perfumes remain known, but some estimates suggest that he composed more than 300. Among his greatest perfumes are “L’Heure Bleue” (1912), “Mitsouko” (1919), “Shalimar” (1925), “Vol de Nuit” (1933), etc.

Although his work earned him universal fame, a considerable fortune, and honors such as Knight of the Legion of Honor, Jacques Guerlain was discreet and did not give interviews. Consequently, little information has reached us about his creative process or his personal life.

Many of his major works are archived in their original form at the Osmothèque which is part of the Versailles Perfumery School, created by Jean-Pierre Guerlain. They are also presented (50 perfumes re-weighed by Thierry Wasser and Frédéric Sacone) on the Champs-Élysées and offered for discovery in the Vintage workshop “Once upon a time…”.

Youth and Apprenticeship

Jacques Guerlain, the second child of Gabriel and Clarisse Guerlain, was born in 1874 in the family villa in Colombes. He was educated in England, in the family tradition, then in Paris at the École Monge, where he studied history, English, German, Greek, and Latin.

His uncle, the perfumer Aimé Guerlain, was childless, so he trained Jacques from the age of sixteen as an apprentice and successor. In 1890, Jacques created his first perfume “Ambre”. He was then trained in organic chemistry at Charles Friedel’s laboratory at the University of Paris, before being officially employed in the family business in 1894.

He experimented widely in both fields: cosmetic products and perfume. He developed a method for scenting ink, while helping with a publication with Justin Dupont regarding various essential oils.

During this period, he composed his first works such as “Le Jardin de Mon Curé” (1895). From 1897, and for two years, Jacques and Pierre shared the responsibilities of manager and head perfumer, until Jacques assumed the role fully in 1899.

The Belle Époque and World War I

At the Universal Exhibition of 1900, Jacques Guerlain presented the floral leather “Voilà Pourquoi j’aimais Rosine” in homage to Sarah Bernhardt (born Rosine Bernhardt), a friend of the Guerlain family.

The perfume named “Fleur qui meurt” (1901) was a new experiment around violet (created in perfumery by synthesis, because its essence cannot be extracted), a fairly recurring accord in Guerlain’s work, soon followed by a duo “Voilette de Madame” (1904) and “Mouchoir de Monsieur” (1904), (created for a couple of friends of the Guerlains).

The latter being one of his rare masculine creations and largely similar to that of his uncle: “Jicky” (1889) with which it shares the Fougère accord (created by Houbigant).

In 1905, Jacques Guerlain married Andrée Bouffait, a Protestant from Lille, which earned him excommunication from the Catholic Church. Their first child, Jean-Jacques, was born the following year.

Après l’Ondée (1906)

Jacques Guerlain finished “Après l’Ondée” (1906), his first major commercial success. This rather melancholic perfume is a tribute to nature after the rain, a variation around heliotrope and violet notes, and it was one of the first or the first to contain a brand new molecule, anisic aldehyde.

This floral bouquet is also sublimated by eugenol (spicy note) and an overdose of powdery notes coming from iris root. It was considered a major work, including by perfumer Ernest Beaux. Après l’Ondée is the perfume that would later inspire “L’Heure Bleue”.

Oriental and Artistic Influence

Kadine, (a title designating the wives of an Ottoman sultan) released in 1911, was one of the first Guerlain perfumes to celebrate the Orient, a few years after “Tsao Ko” created in 1898. This theme would inspire a large part of his work.

He was fond of oriental art, such as celadon and Blanc de Chine which he collected to decorate his apartment at Parc Monceau at 22 rue Murillo. An aesthete with very eclectic taste, Jacques Guerlain was a collector of Nevers and Rouen faience.

He appreciated furniture by André Charles Boulle and Bernard van II Risamburgh (since bequeathed to the Louvre), paintings by Francisco Goya, Edouard Manet, and Claude Monet (including The Magpie, also bequeathed to the Louvre). He found that Impressionist paintings were charming in children’s rooms!

L’Heure Bleue (1912) and the Premonitions of War

Guerlain’s passion for Impressionism and its evening effects certainly influenced “L’Heure Bleue” (created in 1912), a metaphor for Paris at the end of the Belle Époque and the period preceding the First World War. Jacques Guerlain’s grandson and successor, Jean-Paul Guerlain, explains it thus:

“Jacques Guerlain said he had a premonition of what was going to happen in Europe. I couldn’t put this emotion into words, I wanted to capture these last moments of beauty and calm before the calamity of war. I felt something so intense, that I could only express it in a perfume.”

On the eve of the outbreak of World War I, Guerlain launched “Le Parfum des Champs-Elysées” (1914), a leathery floral, to inaugurate the boutique at 68 avenue des Champs-Élysées. It was sold in a turtle-shaped bottle, which was reportedly chosen on purpose as a message addressed to the boutique’s architect, Charles Méwès.

Indeed, Jacques Guerlain found that the Champs-Élysées building was being built too slowly (a whole year)! This same magnificent bottle was reissued in Black crystal upon the reopening of the Maison des Champs-Élysées in 2015, following the work done by architect Peter Marino.

Jacques Guerlain was mobilized shortly after. At that time, he was 41 years old and already the father of three children (he would have five). While serving in the war, he suffered a head injury that left him blind in one eye and thus he returned home.

Unable to drive again, his wife began driving him. Impossible now to ride a horse and his taste for hunting left him too. His weekends were spent with his family and dogs on his parents’ property, in the Vallée Coterel, a beautiful residence built in the Mesnuls estate.

In 1916 his mother, Clarisse, passed away at the age of 68. Jacques Guerlain launched a perfume during the war “Jasmiralda”, woody jasmine referencing Marius Petipa’s heroine “La Esmeralda”.

Interwar Period: Exoticism and Masterpieces

“Mitsouko” was created in 1919, and is the result of several hundred trials with oakmoss (today replaced at Guerlain by natural moss from another tree) and the peach scent gamma-undecalactone, also called C14.

Named after Claude Farrère’s heroine in the novel “La Bataille” (1909), the perfume expresses Jacques Guerlain’s considerable attraction to Asia and particularly Japan.

“Mitsouko”, an imposing chypre, was also considered the archetype of the new post-war woman, an emancipated woman, (who replaced men during the war) in contrast to his pre-war perfume “L’Heure Bleue”, an essentially soft amber floral with its velvet base.

It is said at Guerlain that “L’Heure Bleue” and “Mitsouko” have the same bottle as if to open and close the parenthesis between the beginning and the end of the war. (I think that during this period, it must have been difficult to develop a new bottle design).

Shalimar (1925)

In 1925, Jacques Guerlain presented his magnificent opus: “Shalimar” at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, of which Pierre Guerlain (Jacques’ brother) was the vice-president. The perfume paid homage to the eponymous Mughal gardens of Northern India. It was the culmination of four years of work. He was fifty years old.

“Shalimar” became the “oriental” archetype of perfumery, and remains the House’s best-seller. Here are the words of a famous perfumer: “Who does not know the intoxicating sillage of Shalimar?”. The bottle created by Raymond Guerlain in collaboration with Baccarat designer, Monsieur Chevalier, received the first prize at this international exhibition.

Djedi, Liu, Vol de Nuit

Guerlain continued to push boundaries the following year releasing “Djedi” (1926), referencing the magician of the Westcar Papyrus and then “Liu” (1929), name of the slave in Puccini’s opera, Turandot, which reflects Guerlain’s admiration for the composer, and which was his first aldehydic floral, born it is said at Guerlain (from a contest with Ernest Beaux creator of Chanel No. 5).

In 1932, Guerlain became a member of the audit committee of the Banque de France and would remain a member of this bank and advisor for the next twenty years.

In 1933, Guerlain created “Vol de Nuit”, a rather dark work. The perfume took its name from the novel “Night Flight” (1931) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (a personal friend of Guerlain), based on the author’s experience in the world of airmail.

That year, Jacques Guerlain’s father, Gabriel, with whom he had long worked, died at the age of 92 in Les Mesnuls. Guerlain then inherited his father’s country house and his stud farm: the Haras de la Reboursière et de Montaigu.

In the following years appeared “Sous le Vent” (1934), referencing the Leeward Islands and created for Josephine Baker (a custom perfume), followed by “Coque d’Or” (1937), inspired by Diaghilev and the creation of the ballet taken from Rimsky-Korsakov’s work “The Golden Cockerel”, for the Ballets Russes.

World War II and Final Years

At the outbreak of World War II, Jacques Guerlain’s youngest son, Pierre, then 21 years old, was mobilized and mortally wounded in Baron along the Oise river. Guerlain was deeply devastated and stopped creating for two years, also abandoning his stud farm in Normandy. He then cultivated fruits and vegetables which he sent to his factory workers.

In 1942, Guerlain returned to creation with the perfume “Kriss”, named after an Indonesian dagger. The Company’s factory in Bécon-les-Bruyères was destroyed by bombing the following year.

Then, as the war was drawing to a close, Guerlain fell into a deep depression. He reissued “Kriss” in 1945, renamed “Dawamesk”, the name coming from a hashish preparation.

He continued to work for the last eighteen years of his life, although he gradually slowed the pace of his creations. Little by little, he retired to his property in Les Mesnuls, and devoted his time to his flower beds, his orchards, and his Japanese garden.

His final creations include “Fleur de Feu” (1948), a fresh and aldehydic perfume, and, four years later, the perfume “Atuana” (a variant spelling of Atuona), the Pacific island identified as the final resting place of painter Paul Gauguin.

“Ode” (1955), Guerlain’s swan song created with his grandson and successor Jean-Paul Guerlain, is a classic floral in homage to his gardens.

Guerlain worked in two laboratories and factories; the first was in Bécon-les-Bruyères destroyed by the war in 1943, and the second in Courbevoie, built in 1947. Our Perfume factory is now located next to Les Mesnuls in Orphin. And recently the cosmetics one opened next to Chartres: called La Ruche.

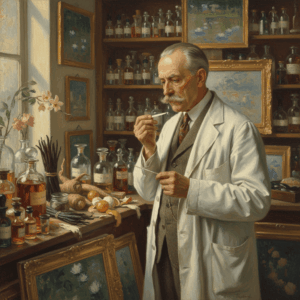

In 1956, Jacques Guerlain reluctantly agreed to be photographed in his laboratory and country house by Willy Ronis for a special edition in Air France’s magazine. These photographs, taken at the end of Jacques Guerlain’s career, offer a rare glimpse into his professional and personal life.

He worked with his grandson on “Chant d’Arômes”, released in 1962; Jacques Guerlain then found himself unfit for creation and declared to his grandson “Unfortunately, I create nothing but perfumes for old ladies.”

Jacques Guerlain died in Paris on May 2, 1963, at the age of 88. Although not a practicing Catholic, his funeral took place at the Saint-Philippe-du-Roule church two days later. He was buried alongside his son, Pierre, and his father in the Passy cemetery.

Influences and Legacy

He closely watched François Coty’s creations. “L’Origan” (1905) is often cited as Guerlain’s basis for “L’Heure Bleue” (1912). But let’s not forget that he created in 1906, “Après l’Ondée”, prelude to this ode to nature.

“Chypre” by Coty (1917), model for “Mitsouko” (1919). But let’s not forget that Guerlain launched much earlier, in 1909, “Chypre de Paris”, and what about “L’Eau de Chypre”. You can see in the previous post on vintages that Guerlain’s Chypre de Paris already possessed a so-called “chypre” accord with bergamot, rose, and mosses.

Admittedly, to my knowledge, it does not possess cistus labdanum, but on the other hand calamus. I think that Coty’s Chypre was a commercial success and possessed a more accomplished Chypre accord.

“Émeraude” by Coty (1921) inspiration for Shalimar (1925). But let’s not forget the creation of the oriental accord in Jicky, in 1889, and of “Sillage” in 1907 which already presents all the beginnings. So the answer is not obvious! Will does not quite share my opinion but you can see on Wikipedia, his original version in English.

Ernest Beaux declared regarding Shalimar: “With the ton of vanillin that Jacques Guerlain used, we could barely make a sorbet. Guerlain, he made a marvel!”. Guerlain admired Paul Parquet, whose influence at the time is undeniable.

The Guerlinade and Fetish Materials

Described as a “virtual pastry chef” by critic Luca Turin, J. Guerlain developed a rich palette of sweet and creamy notes, which he mixed with those of his uncle and predecessor, Aimé Guerlain, based on amber notes. These notes are a style, a signature called “Guerlinade”.

Jacques Guerlain was also a pioneer in the use of green notes, such as galbanum which was considered very bold for the time, found in: Vol de Nuit and in Sous le Vent.

They can be considered precursors of Perfumes such as the one created by Paul Vacher, Miss Dior in 1947. Some perfumers also think there is a correspondence between Sous le Vent and Dior’s Eau Sauvage.

Certain materials are omnipresent in Guerlain’s work, a high quality of citrus fruits (bergamot, lemon, sweet mandarin, and bitter orange), coumarin, floral absolutes (cassie, jasmine, rose, orange blossom), green notes (galbanum), violet (ionones), and the finest qualities of iris, vanilla, and ylang-ylang.

He had a penchant for aromatic spicy notes (cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg) and certain herbs of Provence (absinthe, angelica, basil, bay leaf, cumin, coriander, tarragon). He was a specialist in aromatic resins (benzoin, labdanum).

Indeed he used opoponax in most of his formulas, sometimes in minute quantities – imperceptible in themselves but indispensable to the overall texture of the perfume. His base notes often consisted of large doses of artificial musks (musk ketone, musk ambrette, musk xylene), which he made great use of, as well as ambergris.

Like François Coty and Ernest Daltroff, Guerlain frequently incorporated bases produced by M. Naef and the Fabriques de Laire, particularly from the latter, the Mousse de Saxe to create a distinctive leather accord. He was also a friend of Louis Amic and Justin Dupont, both at Roure-Bertrand with whom he signed an exclusivity agreement for certain molecules used again like the ethylvanillin employed in Shalimar.

J. Guerlain’s technique was knowing how to balance synthetic molecules and natural notes, which is considered exemplary. As an independent perfumer, J. Guerlain experienced total creative freedom.

“Jacques Guerlain worked like a portrait painter at his easel,” wrote Jean-Paul Guerlain, “and when the creation was finished, he chose a bottle – as a painter would choose a frame – and he offered the new perfume for sale in the Boutique without further delay.” Often, he would go down to the boutique to ask the opinion of loyal customers.

His creative process varied greatly depending on the work in question; some of his formulas are relatively short, including that of “Mitsouko” (1919). Others are more elaborate, sometimes integrating previous perfumes (called “drawer formulas”); “Cuir de Russie” (1935) counts among its ingredients “Le Chypre de Paris” (1909) and “Mitsouko”.

Guerlain’s faithful muse, it is said, was his wife, Andrée, affectionately nicknamed Lili, for whom he notably created “Cachet Jaune”.

“Remember one thing,” said Jean-Paul Guerlain his grandson: “One always creates perfumes for the woman with whom one lives and whom one loves.” Guerlain spoke little of his work and creative process. Indeed, he was quite taciturn. J. Guerlain, speaking of the creative process of a fragrance, simply replied: “Perfumery? It is a question of patience and time.”

A Lasting Legacy

Unlike François Coty, Ernest Daltroff, or Paul Parquet, self-taught perfumers who revolutionized Perfumery in the early 20th century, Jacques Guerlain distinguished himself by his astute discernment and his wary traditionalism, undoubtedly influenced by the weight of the family legacy.

Marcel Billot, founding president of the French Society of Perfumers, aptly described J. Guerlain as “A genius who knew how to be of his time while nevertheless living in conformity with tradition.”